Submitted by Gregg Tripoli, OHA

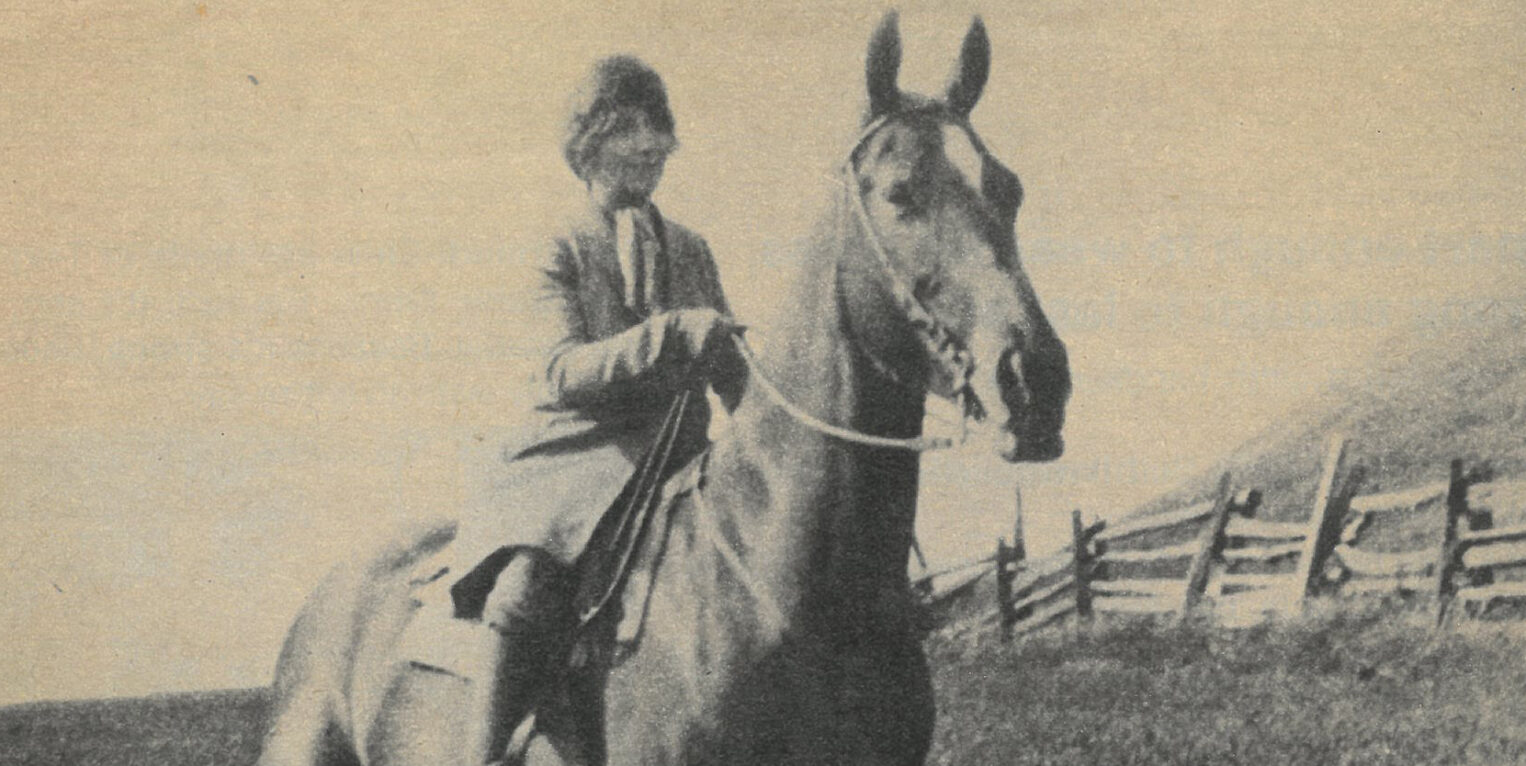

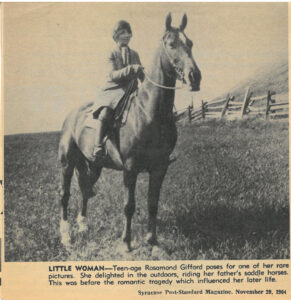

Rosamond Gifford

(1873 – 1953)

Rosamond Gifford was definitely an enigma. Her attorney father, William, and her mother separated when Rosamond was just a child and she lived, for the most part, with her mother in Tully. She attended a boarding school in Boston, where she supposedly lived under the assumed name of Violette LaVigne and married an abusive, womanizing, alcoholic gambler from Montreal who went by the name of Alfred LaFayette (also not his real name) in 1895 when she was 22. They divorced five years later and she retained her maiden name and returned to Tully.

In 1904, when she was 31, her father suggested she return to Boston and study music (a passion of hers) in the hope that she could earn a living at it and become self-sufficient. She did so and studied the concert harp until she became proficient enough to begin giving lessons. She lived frugally on rent from some property her mother gave her, combined with the income from 100 shares of Goodrich Rubber stock her father had given her, and the income from the Harp lessons she taught.

After her mother died in 1912, she returned to Tully to settle the estate and, at her father’s urging, she sold her mother’s house and moved in with her father on a large farm he owned in what is now the area of Dewitt.

To understand Rosamond, it’s important to know a bit about her father, William. He spent most of his time and energy building his financial estate and, though he had plenty of money, he lived rather simply and often felt guilty about his one pleasure, which was raising trotting horses, because they didn’t make him any money. In fact, in his letters to Rosamond, while trying to convince her to move to the farm, he expressed his concern over her ability to make any real money by giving harp lessons, likening her love of music to his love of trotters, referring to such activities as “chasing shadows.”

His motto was “live like a hermit and work like a horse.” He was also constantly worried about how his legacy would be maintained and once wrote to her about a friend of his who had worked hard and left a fortune that was squandered by his heirs.

William enticed Rosamond to move to the farm with a contract that he put in writing dated May 31, 1913 promising that, if she took care of the farm and managed it for him, he would leave her his entire estate when he died. She agreed and William retired to a home he kept in Syracuse, where he suffered a debilitating stroke a few months later.

By all accounts, Rosamond kept her end of the bargain. She was a hard worker and an excellent manager. She began to live by her father’s motto, living like a hermit and working like a horse and the farm flourished. Unbeknownst to her, however, her father, two years after his agreement with Rosamond, drew up a will that, essentially, changed the terms of their 1913 agreement. Instead of giving her his entire estate, he set up a trust, which would provide an income for Rosamond of $60,000 per year for 10 years, after which she would receive the entire estate.

Rosamond found out about the will when her father died in 1917 and she sued the trust and its executors and won, inheriting just over $1,000,000 (equivalent to approximately $16,700,000 in today’s dollars).

Rosamond worked the farm until 1929, when she divided the property into tracts and sold the land (part of which is now occupied by LeMoyne College). She moved to a large house with a barn on the shores of Oneida Lake and lived a very isolated life, though she kept in close contact with her lawyer and banker, visiting them once a week in her truck, which was driven by her caretaker. One news report from the time recounts that her standard dress for these outings was a leopard skin coat and riding boots. The large home she lived in was very sparsely furnished and her bedroom was the only furnished room on the second floor. When Rosamond died in 1953, her executors had to borrow chairs to hold her very small funeral in the home. The barn contained 33 goats, whose milk was used to feed her over 50 cats (as well as Rosamond herself, who was a great proponent of goat’s milk).

Rosamond worked the farm until 1929, when she divided the property into tracts and sold the land (part of which is now occupied by LeMoyne College). She moved to a large house with a barn on the shores of Oneida Lake and lived a very isolated life, though she kept in close contact with her lawyer and banker, visiting them once a week in her truck, which was driven by her caretaker. One news report from the time recounts that her standard dress for these outings was a leopard skin coat and riding boots. The large home she lived in was very sparsely furnished and her bedroom was the only furnished room on the second floor. When Rosamond died in 1953, her executors had to borrow chairs to hold her very small funeral in the home. The barn contained 33 goats, whose milk was used to feed her over 50 cats (as well as Rosamond herself, who was a great proponent of goat’s milk).

Rosamond was a tough, no nonsense woman, there’s no doubt about it. She fought a few high profile court battles in her lifetime over money and she was just as protective of her nest egg as her father was about his. She absolutely hated the IRS (known then as the Internal Revenue Bureau) and she often wrote her tax payment checks to the INFERNAL Revenue Bureau.

By the time of her death, she turned the $1,000,000 that her father took a lifetime to build into an estate worth $6,000,000 (the equivalent of just over $48,000,000 today) and she gave almost every penny of it to establish a charitable corporation.

We have no record of Rosamond’s involvement in, or contributions to, any charities while she was alive. One article mentiones that she gave anonymously and, of course this is possible, though we do know that, like her father, she was fiercely committed to wealth accumulation. Her will does not specify any particular organization or field of interest stating that the corporation should benefit “religious, educational, scientific, charitable, or benevolent causes”. Did Rosamond give her money to charity in order to keep it out of the hands of the IRS? One can only guess.

What we do know is that the Gifford Foundation has been tremendous stewards of her money and has benefited countless organizations and worthy causes. Both William and Rosamond Gifford would be very pleased to know that their nest eggs were certainly not squandered. And Rosamond would be particularly pleased to know that not one penny went to the “Infernal” Revenue Bureau.